She closes her eyes. Her breath, initially uneven, begins to find a rhythm. With her arms crossed over her chest, she taps each shoulder in a slow, alternating beat—left, right, left, right—like the wings of a butterfly coming to rest. She’s alone in her bedroom, but she isn’t unaccompanied. Her therapist watches quietly from a laptop screen.

This is not a ritual, nor a prayer, though it holds elements of both. It’s a technique—a gesture of gentle repetition used by trauma therapists worldwide. It’s called the Butterfly Hug.

Born in the chaos of a natural disaster, the method has traveled continents, crossed language barriers, and landed in the hands of war survivors, abuse victims, frontline nurses, and ordinary people who carry extraordinary pain. And now, nearly three decades since its quiet inception, the Butterfly Hug has received its first comprehensive clinical codification.

A newly released technical report by its original creators offers not just instructions, but validation: the method is proven to work. Scientifically. Psychologically. Somatically. And in a world where trauma often outpaces available care, this simple, self-directed tool is quietly revolutionizing how people begin to heal.

THE RESEARCH REPORT – CORE FINDINGS

A newly released technical report authored by Drs. Ignacio Jarero, Lucina Artigas, and Benito Estrada offer, for the first time, direct neurobiological evidence of what many trauma clinicians have long suspected: the Butterfly Hug, a self-administered technique within EMDR therapy, not only helps patients cope—it changes the brain.

The authors present compelling data from a functional neuroimaging study exploring what happens inside the brain when trauma survivors use the Butterfly Hug as part of EMDR therapy. The participants: 20 women between the ages of 41 and 68, all diagnosed with cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The protocol followed EMDR-PRECI—a structured, abbreviated EMDR protocol designed for early interventions—and integrated the Butterfly Hug as the method for bilateral stimulation (BLS) during memory reprocessing. Unlike past observational studies, this time the researchers watched the brain in real-time, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Before treatment, when patients were asked to recall the most distressing moments of their cancer experience, brain scans revealed hyperactivation in regions deeply implicated in traumatic stress: the amygdala, insula, hippocampus, and thalamus. At the same time, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)—a brain area responsible for emotional regulation—showed hypo-responsiveness, a pattern commonly seen in PTSD.

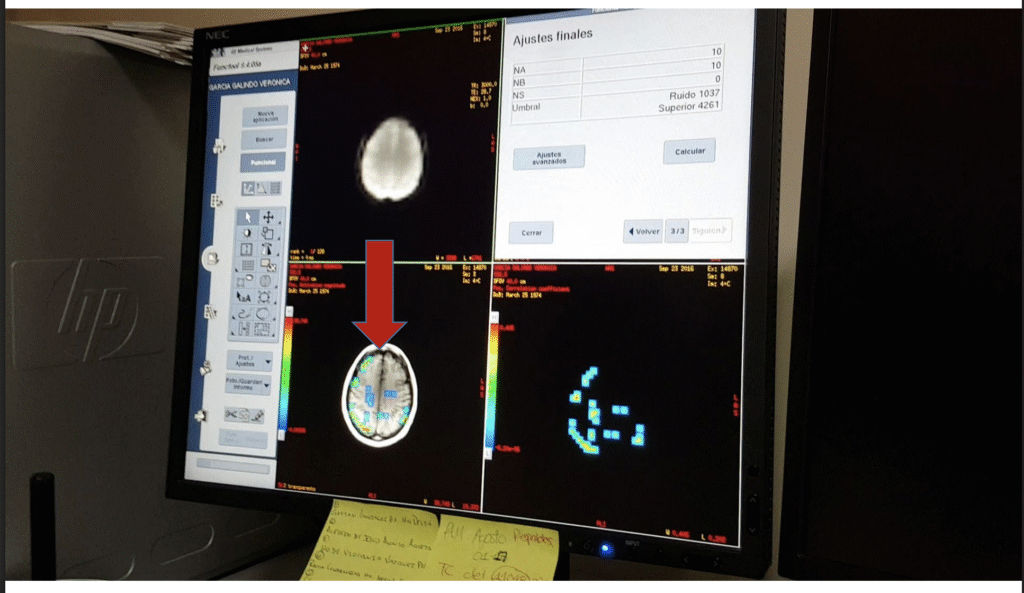

Then, during a 55-minute EMDR session that included the Butterfly Hug, the women engaged in trauma reprocessing while being scanned again. The results were striking: activity in the amygdala decreased, and activation increased in the mPFC, particularly in the anterior cingulate cortex and ventral medial frontal gyrus. These shifts—highlighted by clear changes in oxygenation patterns—suggest a normalization of brain function that aligns with therapeutic recovery.

Even more significantly, these changes were consistent across the group. Time-series data showed neuromodulation in key limbic-prefrontal circuits, implying that the Butterfly Hug wasn’t merely symbolic or self-soothing, but biologically potent.

In the study’s words: “The BH triggered simultaneous changes across multiple brain regions… facilitating emotional stabilization.” The authors conclude that the Butterfly Hug may help restore the brain to its baseline neurobiological state—a feat previously thought to require multiple sessions, medications, or longer-term interventions.

GLOBAL CONTEXT AND RECOGNITION

Long before the fMRI confirmed its effects, the Butterfly Hug had already traveled far, from crowded shelters in southern Mexico to refugee camps in the Middle East, from teletherapy sessions during a pandemic to mental health classrooms in Europe and Asia.

The method was first improvised in 1998, during the aftermath of Hurricane Pauline, when Mexican EMDR therapist Lucina Artigas faced a logistical and ethical challenge: how to deliver trauma care to dozens of children at once, without physical contact. Her solution—asking each child to cross their arms and tap their shoulders, mimicking the wings of a butterfly—would quietly revolutionize how trauma is addressed in mass emergency settings.

Since then, the Butterfly Hug has become a cornerstone of trauma care in humanitarian settings. It’s used by the EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Programs (HAP) in war-torn areas from Gaza to Ukraine, and in post-disaster zones across South America, Asia, and Africa. It has been integrated into EMDR-IGTP (Integrative Group Treatment Protocol), a group-based intervention used by clinicians working with communities affected by mass trauma.

In 2000, the EMDR International Association recognized its significance by awarding Artigas the Creative Innovation Award, delivered in person by EMDR founder Dr. Francine Shapiro. Two decades later, the Butterfly Hug is now standard practice in many group trauma interventions and is taught in EMDR training programs around the world.

More recently, its influence has extended into popular culture. In 2021, Prince Harry was seen using the Butterfly Hug during a filmed EMDR session in The Me You Can’t See, the Apple TV+ mental health series co-created with Oprah Winfrey. His public use of the technique sparked widespread curiosity and lowered stigma, prompting searches and explanations to trend across social media.

In academic settings, universities across Europe, North America, and Latin America have incorporated the Butterfly Hug into psychology curricula and trauma certification programs. It’s increasingly recommended as a self-regulation tool for therapists, students, and patients alike—used between sessions, during crises, or even in moments of quiet, overwhelming feelings.

From a clinical improvisation in a devastated city to a scientifically validated therapeutic gesture, the Butterfly Hug has evolved into more than just a method. It has become a symbol of safety, autonomy, and now, scientifically grounded healing.

EXPERT COMMENTARY AND EMERGING IMPLICATIONS

The findings from the July 2025 neuroimaging study are being welcomed as a milestone in trauma-informed care, particularly by those working at the intersection of neuroscience and psychotherapy.

“This is the first time we have clear, visual, neurobiological evidence of what the Butterfly Hug is doing inside the brain,” said Dr. Ignacio Jarero, the lead author of the report and co-creator of the method. “It is not only helping patients regulate in the moment. It appears to be facilitating long-term changes in how the brain responds to traumatic memory.”

At the heart of the study was a team led by Dr. Benito D. Estrada, who oversaw the fMRI protocols. The imaging revealed predictable shifts: downregulation in hyperactive limbic regions like the amygdala and insula, and increased activation in the regulatory areas of the medial prefrontal cortex.

“We saw consistent neuromodulation in every participant,” Estrada reported. “The Butterfly Hug helped restore functional balance in areas that are typically dysregulated in PTSD. That’s a very promising signal.”

Outside the research team, other experts have taken notice. Dr. Ruth Lanius, a prominent neuropsychiatrist at Western University in Canada, has long emphasized the central role of the medial prefrontal cortex in the recovery from trauma. Although not affiliated with the study, her framework helps contextualize the significance of the results.

“Recovery from trauma requires reestablishing connections between the mPFC and limbic structures like the amygdala,” Lanius wrote in a 2010 paper. “Without that top-down regulation, patients remain stuck in fight-or-flight activation, unable to feel safe.” (Lanius et al., 2010)

While some researchers caution that broader randomized trials are still needed—especially across varied trauma types—many see the current findings as a rare convergence: a technique that is simple, self-directed, and now scientifically grounded.

“The Butterfly Hug is a democratizing tool,” Jarero noted. “It puts a piece of healing directly into the hands of the person who needs it most.”

The images from the study—red fading to blue in the amygdala, with oxygenation increasing in the medial prefrontal cortex—are now being circulated in social media posts by clinicians seeking data to support their intuition.

Several therapists interviewed for this article described the findings as “validating,” “hopeful,” and “a turning point” in low-resource trauma care.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

While the findings of the July 2025 report are compelling, the authors are clear-eyed about the study’s limitations—and the need for deeper exploration.

The research design did include a control condition, allowing the team to compare brain activity during trauma recall with and without the use of the Butterfly Hug. These within-subject comparisons revealed consistent neuromodulatory effects across regions associated with PTSD, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex.

However, the study stops short of being a randomized controlled trial (RCT). It does not compare the Butterfly Hug to other standard forms of bilateral stimulation in EMDR therapy, such as eye movements or auditory tones. Nor does it randomize participants across different intervention arms to test for causal efficacy. That means the unique contribution of the Butterfly Hug—while promising—has yet to be tested against gold-standard controls.

The sample size is another limitation. With only 20 adult women suffering from cancer-related PTSD, the generalizability of the findings remains narrow. Trauma is not monolithic; future studies will need to explore how the method affects survivors of interpersonal violence, combat, natural disasters, and childhood adversity.

Moreover, the neuroimaging data captures only a single session and does not measure long-term effects. The durability of the brain changes—whether they are sustained weeks or months after treatment—remains an open question.

Still, for many in the trauma field, the report represents a watershed moment.

“We saw significant differences between the control condition and the BH intervention,” said Dr. Benito Estrada. “That points to something real happening in the brain. But now we need to explore how long it lasts, and whether it holds across trauma types.”

The authors encourage future research to expand beyond laboratory conditions into community, humanitarian, and digital care settings, where the Butterfly Hug is already being used. Trials with larger, more diverse populations and direct comparisons to other EMDR methods will be essential.

As Dr. Ignacio Jarero notes, “This is not the end of the story. It’s the beginning of a new chapter—one where simple, self-applied techniques may become central to how we treat trauma at scale.”

The Butterfly Hug has always lived in the space between gesture and grace. For decades, its effectiveness was grounded in clinical intuition and field reports—therapists and survivors alike speaking of its calming, centering power. But with this latest study, we are no longer in the realm of anecdote.

We are now observing the brain respond in real-time to a method that requires no equipment, no pharmaceuticals, and no one else in the room. And what it shows is striking: limbic hyperactivation begins to quiet. Regulatory circuits reignite. Patterns of trauma begin to normalize.

For practitioners working in war zones, for clinicians on Zoom calls with isolated patients, for caregivers holding space in schools, hospitals, and shelters—this is not just validation. It’s permission. Permission to trust that even the simplest, most embodied interventions can meet the complexity of trauma with integrity.

“It’s an invitation,” says Dr. Ignacio Jarero. “To rethink what healing looks like—and who gets to access it.”

In a world fractured by displacement, disaster, and disconnection, the Butterfly Hug offers something radical: a trauma tool that does not depend on proximity, power, or privilege. It asks only that a person be willing to cross their arms and begin tapping—a rhythm as old as the heartbeat.

As research continues, and as the method evolves, its symbolism remains as profound as its science: two hands, meeting at the center of the body, not to shield, but to reconnect.

Jarero, I., Artigas, L., & Estrada, B. D. (2025, July). Technical report on the neurobiological insights of the EMDR Therapy Butterfly Hug method for self-administered bilateral stimulation. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393794845

Artigas, L., & Jarero, I. (2000). The Butterfly Hug method. Recognized with the EMDRIA Creative Innovation Award by Dr. Francine Shapiro. EMDR International Association.

Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R. J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C., Bremner, J. D., & Spiegel, D. (2010). The dissociative subtype of PTSD: Rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 27(8), 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20767

Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex. (2021). Demonstrated the Butterfly Hug in EMDR therapy during The Me You Can’t See [TV series]. Apple TV+.

EMDR International Association (EMDRIA). (2020). The EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol (EMDR-IGTP). https://www.emdria.org

Jarero, I., & Artigas, L. (2010). EMDR integrative group treatment protocol: Application with child victims of natural disasters. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 4(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.4.2.123